Posts Tagged ‘Bosnian Muslims’

UN says Serbs guilty of supporting terrorism

Beaver County Times, p.A4

1 September 1994.

SARAJEVO, Bosnia-Herzegovina (AP) – Bosnian Serb leaders are guilty of “state ordained terrorism” in a campaign purging northern Bosnia of thousands of non-Serbs, a U.N. aid official charged today.

Peter Kessler of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, the main U.N. aid agency, said 3,000 Bosniaks had been driven from their homes in Serb-held areas in August alone. Read the rest of this entry »

Bosnian Muslims pressured to baptize during Genocide in Bosnia

Sun Journal

3 January 1994.

By Barbara Demick

Knight-Rider Newspapers

BIJELJINA, Bosnia-Herzegovina — Two months ago, the police paid an unexpected visit to the home of a Bosniak pediatrician and his wife, a dentist. They had bad news. The city wanted to take over their spacious three-story home for municipal offices.

But the pediatrician also had a surprise for the authorities. He pulled out papers showing that he had legally changed his traditional Bosniak name to a Serbian name. Read the rest of this entry »

‘Ethnic Cleansing’ Continues in Serb-controlled Bosnia

A Bosniak family was bomb-attacked by Serb men in Banja Luka… A Croat woman was grabbed from the streets in broad daylight and raped by a gang of Serb men… an elderly Croat woman was attacked in the city center by an assailant who cut off her ears and poked out her eyes… Adina, a 19-year-old Bosniak woman was raped on March 8 by four Serb men in military uniforms…

Gainesville Sun, p.8A

26 March 1994.

By John Pomfret

GASNICI, Croatia — Ismet Hrustanovic had an inkling something was going on in his back yard. The engineer’s puppy started yelping. Twigs and leaves crunched under the heavy feet of men in boots.

Next, a fusillate exploded into his two-story house. One bullet passed through his nose, into his eye socket and out near his ear. Another bored into his wife’s ankle. Several more punched holes in the wall near his 10-year-old son. A final blast killed the puppy.

This is how Hrustanovic, a Muslim [Bosniak], spent Monday, Jan. 31 — hunkered down with a bleeding face while his wife writhed in pain in their modest house in the Serb-held Banja Luka region of Bosnia. On Wednesday, they were evacuated from the region by the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross. Read the rest of this entry »

Serbs Intended & Planned the Destruction of Bosniak People

The aim of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina was to destroy the Bosnian Muslims

Author: Florence Hartmann

Interviewed by Dani (Sarajevo)

Translated by the Bosnian Institute, UK on 16 August, 2007

Florence Hartmann covered the former Yugoslavia for Le Monde, later became the most prominent spokesperson for the Hague Tribunal, and is the author of a study of Slobodan Miloševic Read the rest of this entry »

Resolution Passed: US Congress Recognizes Bosnian Genocide (1992-95)

Whereas

in July 1995 thousands of men and boys who had sought safety in the United Nations-designated `safe area’ of Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina under the protection of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) were massacred by Serb forces operating in that country;

Whereas

beginning in April 1992, aggression and ethnic cleansing perpetrated by Bosnian Serb forces, while taking control of the surrounding territory, resulted in a massive influx of Bosniaks seeking protection in Srebrenica and its environs, which the United Nations Security Council designated a `safe area’ in Resolution 819 on April 16, 1993;

Whereas

the UNPROFOR presence in Srebrenica consisted of a Dutch peacekeeping battalion, with representatives of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the humanitarian medical aid agency Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) helping to provide humanitarian relief to the displaced population living in conditions of massive overcrowding, destitution, and disease;

Whereas

Bosnian Serb forces blockaded the enclave early in 1995, depriving the entire population of humanitarian aid and outside communication and contact, and effectively reducing the ability of the Dutch peacekeeping battalion to deter aggression or otherwise respond effectively to a deteriorating situation;

Whereas

beginning on July 6, 1995, Bosnian Serb forces attacked UNPROFOR outposts, seized control of the isolated enclave, held captured Dutch soldiers hostage and, after skirmishes with local defenders, ultimately took control of the town of Srebrenica on July 11, 1995;

Whereas

an estimated one-third of the population of Srebrenica , including a relatively small number of soldiers, made a desperate attempt to pass through the lines of Bosnian Serb forces to the relative safety of Bosnian-held territory, but many were killed by patrols and ambushes;

Whereas

the remaining population sought protection with the Dutch peacekeeping battalion at its headquarters in the village of Potocari north of Srebrenica but many of these individuals were randomly seized by Bosnian Serb forces to be beaten, raped, or executed;

Whereas

Bosnian Serb forces deported women, children, and the elderly in buses, held Bosniak males over 16 years of age at collection points and sites in northeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina under their control, and then summarily executed and buried the captives in mass graves;

Whereas

approximately 20 percent of Srebrenica’s total population at the time — at least 7,000 and perhaps thousands more — was either executed or killed;

Whereas

the United Nations and its member states have largely acknowledged their failure to take actions and decisions that could have deterred the assault on Srebrenica and prevented the subsequent massacre;

Whereas

Bosnian Serb forces, hoping to conceal evidence of the massacre at Srebrenica , subsequently moved corpses from initial mass grave sites to many secondary sites scattered throughout parts of northeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina under their control;

Whereas

the massacre at Srebrenica was among the worst of many horrible atrocities to occur in the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina from April 1992 to November 1995, during which the policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing pursued by Bosnian Serb forces with the direct support of the Serbian regime of Slobodan Milosevic and its followers ultimately led to the displacement of more than 2,000,000 people, an estimated 200,000 killed, tens of thousands raped or otherwise tortured and abused, and the innocent civilians of Sarajevo and other urban centers repeatedly subjected to shelling and sniper attacks;

Whereas

Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (done at Paris on December 9, 1948, and entered into force with respect to the United States on February 23, 1989) defines genocide as `any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) killing members of the group; (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; and (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group’;

Whereas

on May 25, 1993, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 827 establishing the world’s first international war crimes tribunal, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), based in The Hague, the Netherlands, and charging the ICTY with responsibility for investigating and prosecuting individuals suspected of committing war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions on the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991;

Whereas

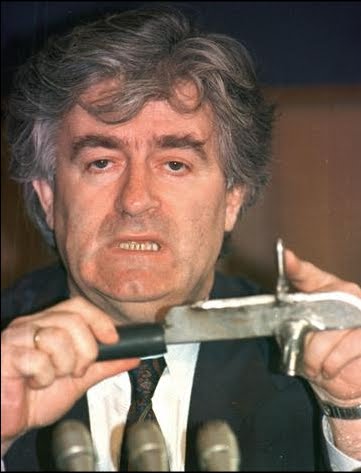

nineteen individuals at various levels of responsibility have been indicted, and in some cases convicted, for grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, violations of the laws or customs of war, crimes against humanity, genocide, and complicity in genocide associated with the massacre at Srebrenica, three of whom, most notably Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, remain at large; and

Whereas

the international community, including the United States, has continued to provide personnel and resources, including through direct military intervention, to prevent further aggression and ethnic cleansing, to negotiate the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (initialed in Dayton, Ohio, on November 21, 1995, and signed in Paris on December 14, 1995), and to help ensure its fullest implementation, including cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved,

That it is the sense of the House of Representatives that–

(1) the thousands of innocent people executed at Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina in July 1995, along with all individuals who were victimized during the conflict and genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995, should be solemnly remembered and honored;

(2) the policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing as implemented by Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995 meet the terms defining the crime of genocide in Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide;

(3) foreign nationals, including United States citizens, who have risked and in some cases lost their lives in Bosnia and Herzegovina while working toward peace should be solemnly remembered and honored;

(4) the United Nations and its member states should accept their share of responsibility for allowing the Srebrenica massacre and genocide to occur in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995 by failing to take sufficient, decisive, and timely action, and the United Nations and its member states should constantly seek to ensure that this failure is not repeated in future crises and conflicts;

(5) it is in the national interest of the United States that those individuals who are responsible for war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity, and grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, should be held accountable for their actions;

(6) all persons indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) should be apprehended and transferred to The Hague without further delay, and all countries should meet their obligations to cooperate fully with the ICTY at all times; and

(7) the United States should continue to support the independence and territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, peace and stability in southeastern Europe as a whole, and the right of all people living in the region, regardless of national, racial, ethnic or religious background, to return to their homes and enjoy the benefits of democratic institutions, the rule of law, and economic opportunity, as well as to know the fate of missing relatives and friends.

Attest:

Clerk.

H. Res. 199

In the House of Representatives, U.S.,

[Passed on] June 27, 2005.

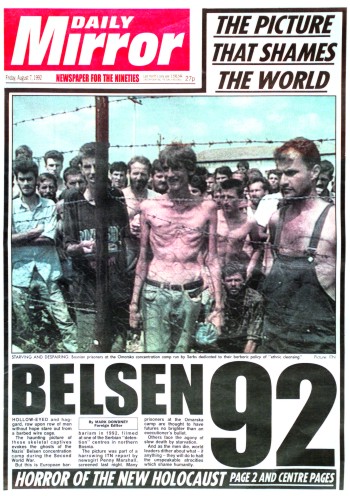

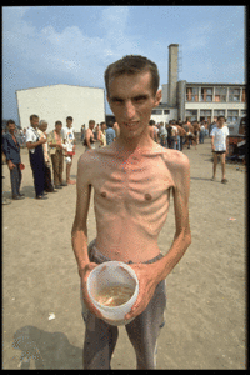

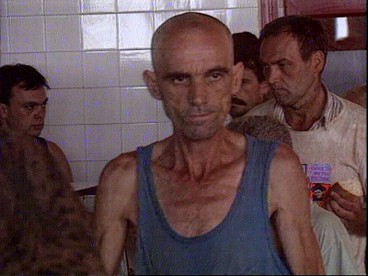

Besieged Srebrenica Resembled Nazi Concentration Camps

Starving Bosniak Refugees Tell of Horror

Starving Bosniak Refugees Tell of Horror

Record-Journal, p.3

13 March 1993.

TUZLA, Bosnia-Herzegovina (AP) — The first emaciated wounded and sick arrived Friday from besieged Srebrenica, leaving behind near-starvation and desperate hardship, including amputation without anesthetic.

Doctors at Tuzla’s main hospital said 12 of the worst cases were flown in by Bosnian military helicopter from the Muslim-held enclave in eastern Bosnia.

A similar airlift two days ago evacuated eight wounded soldiers from the eastern Bosnian front, but Friday’s arrivals were the first from Srebrenica proper, a focus of U.N. relief attempts.

“All the time I was thinking of getting away to somewhere where I could heal,” said Sead Klempic, his bones throwing sharp contours into the blanket covering his wasted body. He was left paraplegic by shrapnel to the spine.

“It kept me alive,” he said. Read the rest of this entry »

Ghettos for Jews and Bosnian Muslims

50 years of European progress:

Polish Jews: In 1943, some 400,000 Jewish people were rounded up and herded into the Warsaw Ghetto. German Nazis starved them and murdered many of them – just because they were Jewish.

Bosnian Muslims: In 1993, some 80,000 Bosnian Muslims were herded into the enclave of Srebrenica. Serbs starved the Bosniak civilians, tortured them, terrorized them, and attacked them on a daily basis from nearby Serb village – just because they were Muslims.

It was genocide: In 1993, two years before the Srebrenica massacre, the United Nations Security Council Resolution 819, adopted unanimously on April 16, 1993, Resolution 819 describing the situation in Srebrenica as a “slow-motion proces of genocide.” With the fall of the enclave two years later, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice ruled it was Genocide.

Photo memory of the Brcko massacre in the Bosnian Genocide

A sequence of photographs showing murders of Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) civilians by local Serb police officer Goran Jelisic. Jelisic was apprehended by a Team of US Navy SEALs (as a NATO SFOR Team) in January 1998. He was sentenced to 40 years imprisonment. Other photographs show mass graves of more than 3,000 Bosniak residents, slaughtered by Serbs, in and around Brcko during the 1992 Bosnian genocide.

Photo evidence courtesy: The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at the Hague (ICTY).

Photo evidence courtesy: The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at the Hague (ICTY).

Witness: Serbs Killed 1,350 Bosniak Prisoners in Brcko camp

“They raped one woman whose children and parents were present, along with everyone else… They took 15 people out and slit their throats on the grass… Three people who were watching at the window and were noticed by the guards, their throats were slit as well. With my own eyes I have seen this… I will forever remember [my friend’s] screaming and yelling not to kill him, and not to slit his throat” – Alija Lujinovic, Bosnian Genocide survivor.

Bosnian Muslim Describes Slaughter by Serbs

(Click to Enlarge) Bosnian Genocide (1992): Bosnian Genocide (1992): A 1992 photographs of mass grave in the area of Brcko showing a Bimeks truck (in the top right-hand corner). The trucks were believed to have been used to transport bodies. Bosniak (Bosnian Muslims) victims tied, killed and thrown into mass grave.

WASHINGTON — A 53-year-old Muslim from Bosnia-Herzegovina on Wednesday said Serbian guards at a detention camp systematically slaughtered 1,350 captives during seven weeks of terror in May and June [1992] (see some of the killing in action)

Alija Lujinovic, who is from the town of Brcko in northeast Bosnia, told his horrific tale to a closed-door session of the Senate Armed Services Committee, then again to reporters at a news conference.

Committee Chairman Sam Nunn, D-Ga., said he did not present Lujinovic at a public hearing because his staff had not had adequate time to corroborate his story. But he said “a lot of the things he’s saying are consistent with other reports… including intelligence.”

Lujinovic, a traffic engineer who denied any involvement in politics or violence, said he was captured May 3 [1992] while hiding in a cellar after Serbian irregulars and troops of the former Yugoslav army attacked his town. Read the rest of this entry »

Bosnian Muslims and Jews have a joint experience of persecution and genocide in Europe

Bosnian genocide mass grave at Pilica farm near Srebrenica, twenty feet deep and a hundred feet long, was excavated by forensic pathologists in 1996. Bosniak victims were blindfolded with hands tied behind their back. Photo by Gilles Peress (from The Graves: Srebrenica and Vukovar (Scalo Books, 1998)).

Dr. Mustafa Cerić is the Grand Mufti of Bosnia-Herzegovina (leader of Islamic community) and a prominent member of the Committee on Conscience fighting against the Holocaust denial.

Invited by president of Fondation pour la Memoire de la Shoah, David de Rothschild, Reisu-l-ulema Dr. Mustafa Cerić took part today in Paris, the seat of the UNESCO, in the presentation of Projet Aladin, accompanied by some two hundred prominent intellectuals, historians, academics and political personae from thirty countries, most of them from the Islamic world.

The gathering is about cultural and educational initiative for promotion of the Jewish-Muslim dialogue based upon mutual acquaintance, respect and refusal to deny and diminish Holocaust. Hosted by the UNESCO, former President of France Jacques Chirac, Prince El-Hassan bin Talaal of Jordan, former President of Indonesia Abdurrahman Wahid and former German Chancellor Gerhardt Schroeder, project “Aladdin” aims to assist in Muslim-Jewish dialogue so as to remove many a prejudice and stereotype which burden the Muslim-Jewish relations in the world.

“The call of conscience”

A statement, titled “The Call of Conscience”, was adopted to denote the principle of the project: Read the rest of this entry »

Canada Mourns Bosnian Genocide Victims

Canada Commemorates 15th Anniversary of Srebrenica Genocide

(No. 217 – July 10, 2010 – 12:30 p.m. ET) The Honourable Lawrence Cannon, Minister of Foreign Affairs, today issued the following statement commemorating the 15th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre:

“Fifteen years ago, in Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina, more than 7,000 Bosniak men and boys were executed and over 25,000 Bosniaks were forced from their homes by Bosnian Serb forces. This tragic event was the worst crime of its kind to be committed in Europe since the Second World War. Both the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia determined it to be genocide.”

“On this solemn occasion, I wish to extend my condolences on behalf of the Government of Canada to the survivors of this atrocity, as well as to all of those whose loved ones lost their lives or remain missing.” Read the rest of this entry »

War's overlooked victims, Bosnian Muslim Women

Some excerpts from today’s edition of The Economist:

“As the reporting of rape has improved, the scale of the crime has become more horrifyingly apparent (see table). And with the Bosnian war of the 1990s came the widespread recognition that rape has been used systematically as a weapon of war and that it must be punished as an egregious crime. In 2008 the UN Security Council officially acknowledged that rape has been used as a tool of war.”

“As the reporting of rape has improved, the scale of the crime has become more horrifyingly apparent (see table). And with the Bosnian war of the 1990s came the widespread recognition that rape has been used systematically as a weapon of war and that it must be punished as an egregious crime. In 2008 the UN Security Council officially acknowledged that rape has been used as a tool of war.”

“At worst, rape is a tool of ethnic cleansing and genocide, as in Bosnia, Darfur and Rwanda. Rape was first properly recognised as a weapon of war after the conflict in Bosnia. Though all sides were guilty [factcheck: there were 20-30 cases of raped Serb women, 20-30 cases of raped Croat women, and close to 20,000 cases of raped Bosniak women], most victims were Bosnian Muslims [Bosniaks] assaulted by Serbs. Muslim women were herded into ‘rape camps’ where they were raped repeatedly, usually by groups of men. The full horrors of these camps emerged in hearings at the war-crimes tribunal on ex-Yugoslavia in The Hague; victims gave evidence in writing or anonymously. After the war some perpetrators said that they had been ordered to rape—either to ensure that non-Serbs would flee certain areas, or to impregnate women so that they bore Serb children.” Read the rest of this entry »

Serbian Myth of Land 'Ownership' of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Special Report

Peace Proposal Provides Serbs Disproportionate Share of Bosnia

By Amira Dzirlo

Washington Report on Middle East Affairs

January/February 1995, Page 16.

The “contact group” draft settlement for Bosnia proposes that the Serbs return to the Bosniaks and Croats about one-third of the Bosnian territory they have occupied. This means that the Serbs would be allowed to keep 49 percent of the territory of Bosnia. These terms have been accepted, reluctantly, by representatives of Bosnia’s Muslims and Croats, but not by the Bosnian Serbs. The unreasonableness of the Serb rejection of the settlement becomes even clearer with a brief review of the history of the Serb land-grab in Bosnia that began during and after World War I.

Among many false Serbian claims in connection with settlement negotiations was the statement that “according to the registry, Serbs own 64 percent of the land of Bosnia-Herzegovina, but they are prepared to return 15 percent of its territory to the Bosniaks out of the total 70 percent which they have captured.”

A Significant Fabrication Read the rest of this entry »

Muslims in Bosnia Converting to Christianity, Fear for Their Lives

New Straits Times

14 December 1993.

BRCKO, Tuesday. — Hundreds of Muslims [Bosniaks] living in Ser-controlled areas in Bosnia have converted to the Orthodox Church and changed their names to distance themselves from their Islamic origins.

But the move in Brcko and surrounding villages is being warily watched by Bosnian Serb authorities worried about its effect on international opinion.

Since January some “hundred people, most of them Muslims” have changed their names, civilian leader Luka Puric told reporters in the north-eastern town of Brcko, 160km west of the Serbian capital, Belgrade. Read the rest of this entry »

The Politics of ‘Neutrality’ in the Bosnian Genocide (1992)

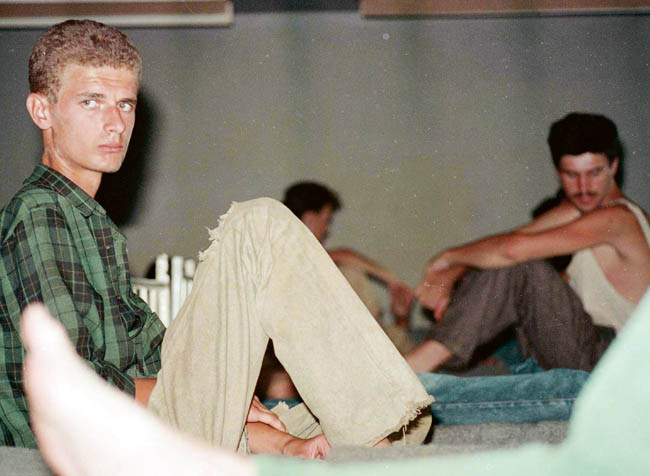

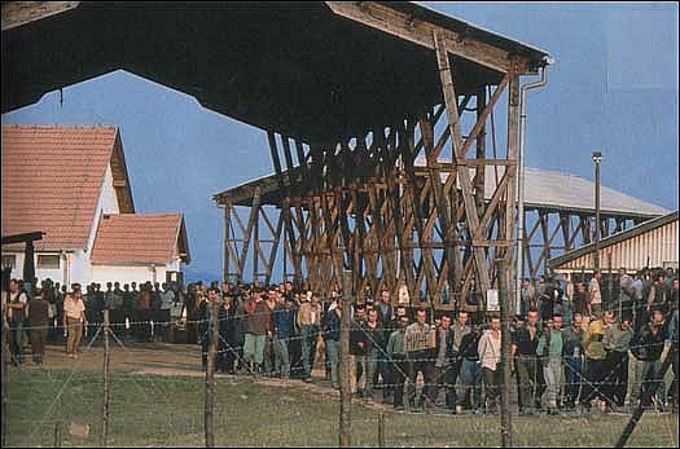

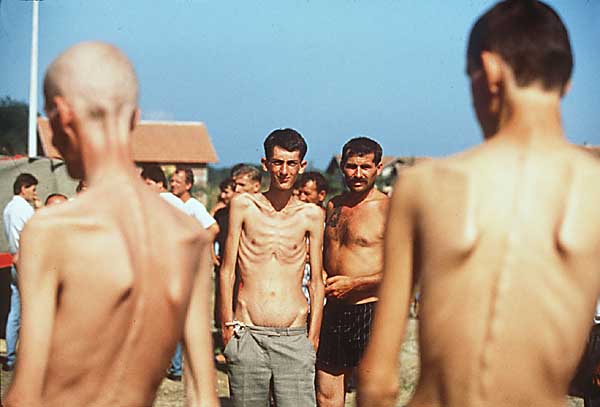

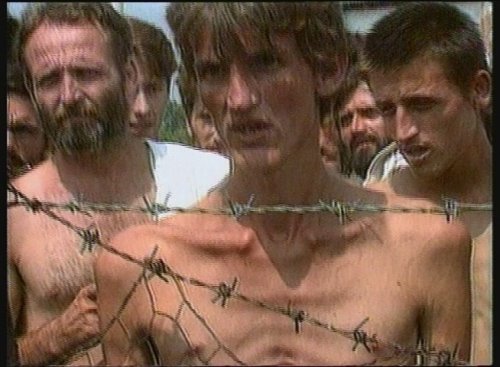

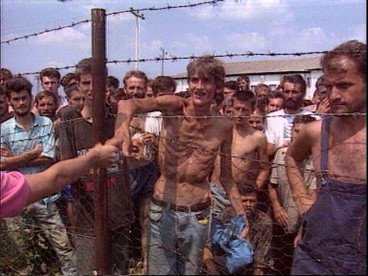

Bosnian Genocide (1992): Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) prisoners in Trnopolje concentration camp near Prijedor. Credits: Ron Haviv, Blood & Honey.

INTRODUCTION:

The Bosnian Genocide is the event referring to brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing of at least 500,000 Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) coupled with the killings of 65,000 to 75,000 Bosniaks during the 1992-95 war of Serbian aggression. There are three legally validated genocides that occurred in Bosnia-Herzegovina, other than Srebrenica. Notable international judgements include: Prosecutor v Nikola Jorgic (Doboj region), Prosecutor v Novislav Djajic (Foča region), and Prosecutor v Maksim Sokolovic (Kalesija/Zvornik region).

All three cases were tried in Germany — at the request of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) — to ease caseload of the ongoing trials at the Hague. Both Nikola Jorgic and Maksim Sokolovic were convicted of genocide (other than Srebrenica); Novislav Djajic was acquitted, but the court confirmed that genocide against the Bosniak population was committed by the Serb forces in eastern Bosnian municipality of Foca. The following is an account of Ed Vulliamy:

“Neutrality” and the Absence of Reckoning:

A Journalist’s Account

By Ed Vulliamy

Text reprinted from the Journal of International Affairs v 52. no. 2 Spring 1999.

On the putrid afternoon of 5 August 1992, I stumbled into Omarska, as a reporter for the Guardian of London, along with a crew from the Independent Television Network (ITN). It was said we had “discovered” Omarska, but this was an inaccurate flattery. Diplomats, politicians, aid workers and intelligence officers had known about the place for months and kept it secret. All we did was announce and denounce it to the world.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) Prisoners in Trnopolje concentration camp near Prijedor.

By remaining neutral, we reward the bullies of history and discard the peace and justice promised us by the generation that defeated the Third Reich. We create a mere intermission before the next round of atrocities. There are times when we as reporters have to cross the line…

During his opening remarks at a recent conference at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Tom Buerghental, chairman of the museum’s Committee on Conscience asked:

How do we explain to our children and grandchildren that in the world in which we live, it is easier to mount a $40 billion rapid response to save the economy of this or that far-away country because its collapse might affect our stock holdings, while we diddle and daddle when it comes to mounting a rapid military response to save people from destruction by a murderous regime?

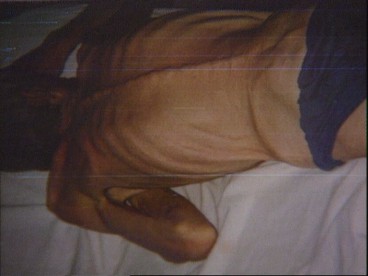

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) Prisoner in Trnopolje concentration camp near Prijedor.

How indeed? How will I explain to my daughter when she is seven years old that a little girl her age died in my arms because, through the sight telescope of the beast who murdered her, she was just a “filthy Muslim,” unfit to live her brief life?

I think the answer to this challenge rests in the entanglement of two notions that are embedded in the Holocaust’s legacy. The first is the notion of “reckoning” — staring history in the face, assigning blame and moral or criminal responsibility. The second is neutrality, the idea that the diplomatic world, like the press, must be detached to do its job properly. In the context of the carnage in Bosnia and the West’s toleration of it, these concepts are vitally important. I believe that history without reconciliation is dangerous history. Crimes against humanity not reckoned with can only lead to more of the same. I also believe that there are moments in history when neutrality is not neutral, but complicit in the crime.

I will argue here that in the examples of Bosnia, Rwanda, Cambodia and elsewhere, the neutrality adopted by diplomats and the media is both dangerous and morally reprehensible. By remaining neutral, we reward the bullies of history and discard the peace and justice promised us by the generation that defeated the Third Reich. We create a mere intermission before the next round of atrocities. There are times when we as reporters have to cross the line, recognize right as right, wrong as wrong and stand up to be counted.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) prisoners in Trnopolje concentration camp near Prijedor. Ron Haviv, Blood & Honey.

A Reporter’s Account

In the winter of 1996 I was asked if I would testify in the case against Dusko Tadic before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague. The ICTY was formed by the United Nations to bring individuals charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity to justice. I was initially wary that the tribunal was no more than a release valve to compensate for the West’s crime of appeasement. Some colleagues who had also worked in Bosnia and whom I greatly admire refused to testify and advised that it was an unwise and perilous course of action. “Our job was to report,” they advised, and if possible, to prompt others to do something that would end the suffering. But justice — the acquittal of the innocent and imprisonment of the guilty — was the business of others. The tribunal was an unknown and potentially dangerous labyrinth. If I testified I would certainly lose any claim to neutrality, if I ever wanted to stake one. The rules are not unlike those of the Mafia; you can say whatever you like about them and they don’t care, but you cross a line once you go into the courtroom.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Covert photograph of beaten inmate at Trnopolje concentration camp. Penny Marshall, ITN, 6 August 1992.

On the other hand, there was an argument with legal and moral components. For example, if I see someone being mugged, I should expect the police to call me as a witness at the mugger’s trial. If the victim is a defenseless child or old lady, one is instinctively more willing to testify. Multiply that reasoning by a factor of a thousand, and you have good reason to testify against genocide in Bosnia. I thought about these arguments carefully. In the end, these were deliberations over what kind of history was being made, over what kind of legacy was left by the camps and ethnic cleansing.

I talked to my father who fought in the Second World War. I was part of a generation and a citizen of a newly unified continent, brought up in the shadow of the Third Reich and in the aura of victory. I had watched at close range, the language and practice of appeasement tear the promises of postwar Europe to shreds. I had watched diplomats obfuscate and lie; I had watched the flag of the United Nations — an icon of this generation — deliver the defenseless people of its own designated safe areas into the hands of butchers. I had watched my own country lead the international community in rewarding the worst violence to blight Europe since Nazi Germany.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Covert photograph of emaciated inmate at Trnopolje. Penny Marshall, ITN, 6 August 1992.

Above all, it seemed to me that the ICTY, for all its shortcomings, was the last organism in the attempt at reckoning in the aftermath of Bosnia’s war. Although Tadic was only a minnow in a war of minnows, this was a war of macabre intimacy in which people knew their torturers. I decided this was a chance for some kind of reckoning for the only people I really cared about — the victims. I threw aside any pretense of neutrality and went to The Hague. I gave the prosecution in the Tadic case all my notebooks and I told them everything I knew.

The Hague, the Netherlands, June 1995.

The breakfast scene resembled what you might find at any other modern Dutch hotel. Corn flakes, cheese, fruit and a generous selection of buns and rolls were arranged on a big table. Waiters and waitresses in pressed shirts and breezy catering-school smiles waited on business travelers enjoying the luxury of company tabs. On this particular morning, a group of guests, noticeably different from the usual clientele, poked at the food with a certain detachment, as though the abundance were somehow unreal, laid out for someone else.

This group from Bosnia was obviously connected by a bond that distanced them from the uniformity of the international hotel. They were mostly men, with one or two women, who looked older than their years. In their speckled brown eyes lay something unfathomable and lachrymal and — whatever this secret was, whatever the bond — it was an unhappy one. The sorrow that sealed it would be told to the world during the days that followed.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) prisoner in Omarska concentration camp near Prijedor.

They were Muslims from northwestern Bosnia, survivors of the Omarska concentration camp. Many had not seen each other since the day after the camp had been revealed to the outside world on 7 August 1992, when it was abruptly closed by its Bosnian Serb management in an attempt to conceal its dark secrets. That day, the surviving inmates of this hell were put on buses and taken to other camps, or deported in convoys across mountains and minefields. Some lucky ones were evacuated to far-flung countries — like Germany, Indonesia or Sweden — that volunteered to take them in.

As was the hallmark of Bosnia’s war, members of their families had been slaughtered, scattered or simply disappeared without trace after the hurricane of violence swept through their villages and towns. Now they exchanged news of who was alive or dead, who had vanished and who had not. They even wondered what had happened to their torturers and the camp commanders and recalled the days when they — inmates and guards — had played soccer together.

(Click to Enlarge Photo) - Bosnian Genocide (1992), Relative of the Omarska concentration camp victims near the Western Bosnian town of Prijedor in Bosnia-Herzegovina holds photos of excavated bodies of her relatives on 06 August, 2006.

They were now assembled to confront the past. These people were called to The Hague to testify before the first international war crimes tribunal convened since the famous Nuremberg trials that had tried and sentenced so many of the orchestrators of the Holocaust. The tribunal’s founders claimed that Nuremberg, in small part, assigned blame for the unimaginable pain of Holocaust survivors, and even liberated the German people from responsibility for the heinous crimes committed in their name. Now the United Nations sought to employ that process in Bosnia-Herzegovina with the ICTY. The tribunal’s first chief prosecutor, Richard Goldstone, said he regarded its work as the difference between peace and an intermission before the next round of hostilities.

Dusko Tadic, a Bosnian Serb, was the first man to be accused at an international court for war crimes since Speer, Goering, Hess and their conspirators. The group having breakfast knew Tadic well, from their lives in both peace and war. When they were asked to point him out, at the end of their testimonies, they did so — some with venom, some with contempt, some barely daring to look him in the eye and still others defiantly. Tadic sometimes looked down or turned his eyes away. Other times he stared back. Once, he looked his accuser in the eye and smiled a devilish grin.

The survivors also testified about Camp Omarska itself. They detailed a place that Western authorities had apparently known about but tolerated and concealed from public knowledge for four long months. It was a place they remembered collectively as well as privately, a place that haunted them now and would follow them forever. After testifying, they walked back to the carpeted lobby and purple uniforms behind the reception desk. Then they took the elevator to wait in room 609, the “witness room.”

The view from room 609 looked out on the North Sea, which rose like a deep blue carpet from the horizon. Beneath the window lay the garden of the modern art museum, landscaped with sculptures. Beyond the museum, people filled bustling cafes, shops and sidewalks lined with flowers. The survivors of Omarska stared out at this for hours, a view across a country whose history was that of the reclamation of land from water. Indeed, the hopeful history of the Netherlands served to deepen the abyss between it and Omarska. It harkened the grotesque proximity, in time and geography, between life in the pretty town below and the camp that we spoke of together for endless hours, smoking cigarettes and remembering. Omarska was a bitter kernel at the heart of both Bosnia’s war and our place in time. A concentration camp in our lifetime, just a few hundred miles down the road from Venice.

Prijedor, Bosnia, August 1992

Though we had been invited to visit the camps by Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, it took five days of haggling with other officers to ultimately gain access to Omarska. The final hurdle was a tedious three-hour briefing at the Prijedor civic center with a group of men referred to as the “Crisis Committee.”

In that meeting, a man who introduced himself as Colonel Vladimir Arsic said it was not possible to go to Omarska. He suggested we visit another camp, Manjaca, which unlike the camps at Omarska and Trnopolje had already been inspected by the International Committee of the Red Cross. Colonel Arsic then gestured to three other men around the table who could grant the necessary permission: Police Chief Simo Drljaca, Mayor Milomir Stakic and his Deputy, Milan Kovacevic. Kovacevic, a bear of a man dressed in a “U.S. Marines” t-shirt, did most of the talking. He was a special expert on concentration camps, he explained, because he had been born in Jasenovac, which was a camp established for Serbs, Jews and Croat dissidents during the Second World War.

After a verbal tug-of-war, the trio of Drljaca, Kovacevic and Stakic agreed we could go. We drove through a ravaged landscape dotted with burned-out houses, but nothing could have prepared us for what we saw as we entered the back gates of the former iron ore mine of Omarska. The scene belonged to some other time. A column of men emerged from a rusty-red hangar, blinking in the sunlight. They were drilled across the yard in single file toward the “canteen” by uniformed guards. The watchful eye of a beefy machine-gunner followed their steps from behind reflective sunglasses. As the men advanced, we could see their skeletal figures, some with shaven heads.

They devoured their watery bean stew, clutching their spoons with rangy fists. They were horribly thin — the bones of their pencil-thin elbows and wrists protruded like pieces of jagged stone through parchment skin. They fixed their huge, hollow eyes on us with hard, cutting stares. There is nothing so haunting as the glare from a prisoner who yearns to tell some truth, but dares not. The guards swung their machine guns, strutting back and forth and listening carefully. “I do not want to tell you any lies,” said one man, his spindly hands shaking, “but I cannot tell the truth.”

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) prisoner Fikret Alic in Trnopolje concentration camp

We had seen very little, but when we tried to see more we were bundled out of the camp and moved on to another vile place: Trnopolje. Here, we met emaciated men crowded behind a barbed-wire fence. They told us of more camps from which they had come, a gulag it seemed. A skeletal man named Fikret Alic told us that at one of the camps, Kereterm, 150 prisoners had been murdered in one night. At Kereterm, he had cried when appointed to load the dead onto trucks.

With the testimony of survivors from a wretched diaspora, the truth that had held the Omarska prisoner silent gradually unfolded. Omarska had been the kind of place where a prisoner was forced to bite the testicles off a fellow inmate who, as he died of pain, had a live pigeon stuffed into his mouth to stifle his screams. One witness at the ICTY trial likened the guards responsible for this barbarism to a crowd at a sporting match. Prisoners, who survived by drinking their own and each other’s urine, were forever being called out of their cramped quarters by name. Some would return caked in blood, bruised and wounded by knives; others would never be seen alive again. Squads of inmates were ordered to load corpses onto trucks. An old man in one makeshift dormitory had tried to keep his son, who had contracted dysentery, alive. But shortly after a beating, the boy died and guards ordered his cellmates to “get rid of this garbage.” Years later, testifying at The Hague, the grieving father would be accused by Dusko Tadic’s counsel of inventing his story. He stared back with righteous outrage: “If I was lying, my son would still be alive,” he said.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Penny Marshall, ITN, 6 August 1992 shakes hand with Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) prisoner Fikret Alic, Trnopolje concentration camp.

The day after we “discovered” Omarska, it was quickly closed and the prisoners transferred so that prying international eyes would not uncover these secrets. At Trnopolje, the barbed wire fence that had penned in Fikret Alic’s group of prisoners was taken down and the camp was renamed “Trnopolje Open Reception Center,” in English, for the benefit of the media circus that descended on the town. Kovacevic was entrusted with the task of explaining to the world what a “reception center” was. He was in a hurry, he said; it was Sunday and he had to go to church.

Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1992-96

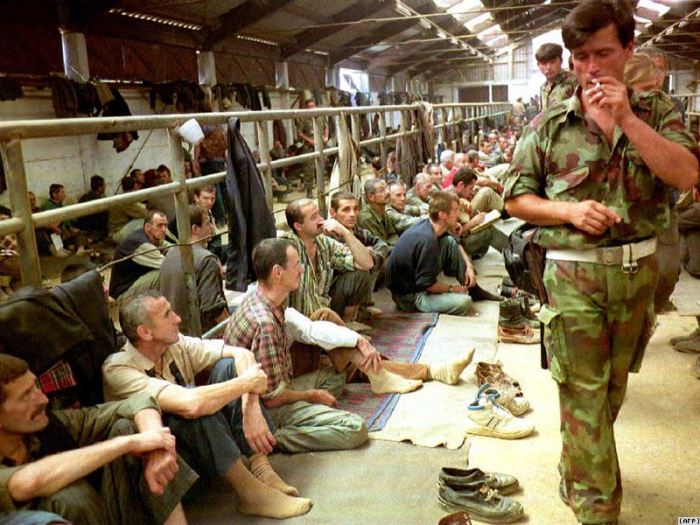

Bosnian Genocide (1992): Bosnian Muslim (Bosniak) prisoners in Manjaca concentration camp near Prijedor.

The camps were just the beginning of the carnage in Bosnia. The ethnic cleansing in camps and villages continued and we saw it from the inside — the “population transfer” alone was terrifying. I accompanied one of the convoys of Muslims from Sanski Most. We were herded in a ramshackle convoy, marshaled by guards brandishing their machine guns, along a mountain road. Knowledge of this route came to be an identifying mark of those who had been in the camps.

We lurched in a convoy of 55 trucks, buses and cars, then cast out on foot across a perilous no man’s land. An hour later our comfortless procession was clambering over a pile of rocks across the road, which marked a makeshift border with the government’s territory, which was surrounded by a carpet of mines. As the guns cracked and crashed around us, we heaved the very young, the very old, their wheelchairs, crutches, babies and teddy bears, over the rocks and carried on. Even the little children were dumb with fear and resolve.

It went on and on — days and weeks stretched into months and years. There was the bloody fall of Jajce, when 40,000 took to the road in flight, under fire, with their herds, horses and carts, arriving in the already swollen town of Travnik. There were the sieges of Maglaj and Bihac, where in 1995 a little seven-year-old girl died in my arms, shot in the head by a Serbian sniper.

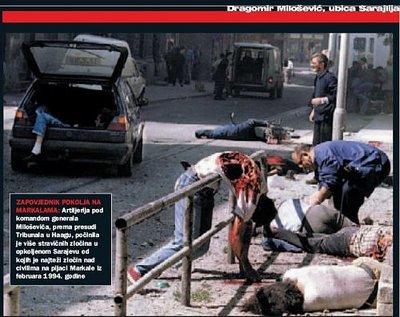

There was Sarajevo, and the sight of the scattered, bloody remains of people who, moments before the merciless shell ripped into them, had been lining up for water at one of the few taps left working in the city. Still worse, there was the Croatian siege of Muslim East Mostar, a slither of land into which 55,000 women and children had been herded and which was leveled into the dust of its own stone by a relentless barrage of some 1,400 shells a day. As their innocent bodies were ripped by red-hot shrapnel, their men were incarcerated in another concentration camp which was my sad honor to uncover — Dretelj. This time, the inmates were again Muslim, but their guards Croat. Most of the prisoners were locked in the dank darkness of two underground hangars, dug into facing hillsides. These men had been locked in for up to 72 hours at a time, sitting in their own diarrhea, without food or water, drinking their own urine for moisture. People back home used to ask if it was “really as bad as the media makes out.” The answer was that it was infinitely worse — we saw only the tip of the iceberg.

Silent Response

I am as convinced now as I was in 1991 that all of this could and should have been stopped by the West at any time. Almost every other reporter who covered the war at close range is convinced of the same. Upon the discovery of Omarska, the leaders of the West professed outrage for a few days, but the real response had been worked out in advance: in essence, do nothing. If “appease” is a pejorative term and offends, then “tolerate” will have to do.

Bosnian Genocide (1995), Srebrenica massacre of 8,000 men and boys, 30,000 women and children ethnically cleansed, many women brutally raped....

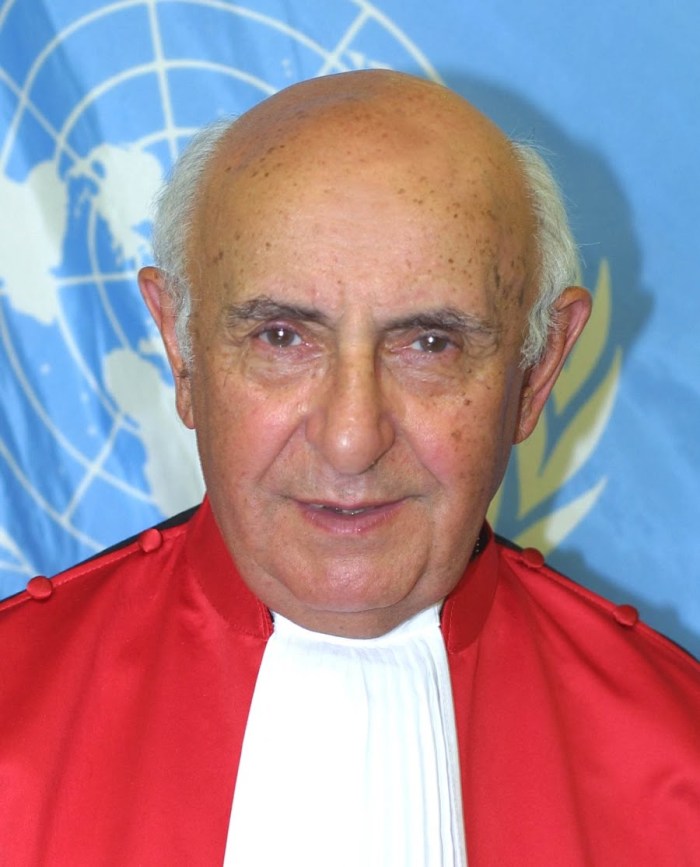

Here is not the place to recount the history of appeasement of the Serbs, for it is the history of the entire war. There were countless moments when the Serbs were told not to cross a line, or face dire consequences if they did. But every time, the bluff was called and the West capitulated with smiles and handshakes. On and on it went, for three long years of empty promises, until the horrible episode at Srebrenica in May 1995 when 8,000 men at a U.N.-designated “safe area” were delivered into the hands of General Mladic’s butchers. Srebrenica is the symbol of our New World Disorder: “Scenes from hell,” said Judge Riad from the bench in The Hague, referring to an old man forced to eat the corpse of his infant grandson, “written on the darkest pages of history.”

Bosnian Genocide (1995), Forensic experts of the International war crimes tribunal inspect remains of the Srebrenica massacre victims in the Pilica mass grave on 24 July 1995.

Deliberate obfuscation by the international community’s spokesmen was essential to international neutrality and constituted the first meddling with the truths of the war to stifle intervention and foster appeasement. The spreading of lies and distortions that would equate aggressor and victim characterized the conflict as a quagmire where civilization would be unwise to intervene. These exercises masqueraded as “neutrality” but transparently advanced the Serbian cause. The term “ancient ethnic hatred” was bandied about as a synonym for “hurricane” or “earthquake,” as if the carnage were a natural phenomenon, inevitable and beyond prevention.

In addition, there was the insistence that the worst massacres in Sarajevo were the work not of those besieging the city, but of those defending it. For example, in the “breadline massacre” of 27 May 1992, 22 people were killed and more than 100 injured while waiting in line for food. The Serbs claimed that the government had bombed their own side. In response to shocking television pictures that showed victims holding their own blown-off limbs, the Serbs issued a press release claiming that the people filmed were cripples who had been given bloodied extremities to hold for the cameras.3 This was then leaked to gullible newspapers that printed front-page headlines such as: “Muslims Slaughter Their Own People.”4 Serbian propaganda served the international community so long as it postponed, or even avoided, a reckoning.

On the Duty of the Press

“Reckoning” is probably the harshest word in the English language. It is something we do in the aftermath of broken marriages or a death in the family. We also try to reckon in the wake of historical calamity, when reckoning means staring the past in the face, coming to terms with what has occurred, settling accounts and asking not only what happened, but why. In such instances, it has different meanings: for the victim, a bitter counting of the cost; for the perpetrator, an acceptance of responsibility. For entire societies, it means a painful and cathartic process. In politics and diplomacy, reckoning means an adjustment of the balance to restore lasting peace, and for the law it means punishing the guilty so that the aggrieved can find justice and relief. Reckoning is a prerequisite for peace; without it, peace cannot breathe. History without reconciliation is dangerous history. The press and individual reporters have a duty to abandon their so-called “neutrality” in order to avert such danger, to reckon with what we witness and to urge others to do the same.

Reckoning cannot come for victims when peace is merely an absence of war, without justice or homecoming. Today, there is a peace of sorts in Bosnia. But it is a peace that recalls the dialogue between Philip II of Spain and Rodrigo Duke of Ponsa in Verdi’s opera Don Carlos. The cynical king boasts of the peace that reigns across his dominion, but the enlightened Rodrigo objects that it is, la pace della tomba — the peace of the grave. It is a peace that recalls the story of a young boy named Jasmin, whom I came to know after the war.

Jasmin was 13 when the war began and his town Zepa was sealed off from the outside world by a noose of Serbian artillery. He was deemed too young to fight, assigned instead to spend the war by a crook in the Drina River, “to get the bodies out, and to give them a decent burial.” For three years, Jasmin rowed a little boat into midstream to haul the bloated corpses — sometimes headless, sometimes child-sized — out of the river to bury them, often under fire, in a makeshift cemetery. Jasmin said he found the bodies beneath the great Ottoman Bridge, the same bridge that spans the Drina at Visegrad, serves as Bosnia’s emblem and is the title of a great work of literature by Ivo Andric, the country’s most celebrated writer. I followed this trail, only to discover that the Serbs had turned Andric’s bridge into a human abattoir. I last saw Jasmin when he was among the lucky refugees to flee Zepa in July 1995. He was evacuated to a mental hospital in Dublin in 1996, at the age of seventeen.

“That bridge will drive me mad,” said a shuddering Hasena Muharenovic, for whom the reckoning can never come. Living in Sarajevo, she recalled how a Serbian squad came for her mother and sister, took them to the bridge, cut them up and threw them off it, along with a carload of others. She bade goodbye to her crippled father, whom she left in an armchair to await his turn and she fled. She was captured and spent the war in a camp with her two young daughters, enduring forced labor and “making coffee” — a euphemism for forced sex with officers. Now, in peacetime, she does not know whether to wait and hope that her husband will return, or give up and leave Sarajevo, killing him in her own mind.

In 1992 14,000 Muslims lived in Visegrad, now there are none. It bothered me that there was apparently no more chance of reckoning among the Serbian victors than among their victims. I remembered the meeting with the so-called crisis committee in Prijedor, with Drljaca, Kovacevic and Stakic on the day we went into Omarska. I recalled the man who had sent us to them, Karadzic’s Vice President, Nikola Koljevic. They were the middle managers of genocide and I wondered what they were thinking. Four years later, I went in search of these men to find out if there was reckoning in Prijedor.

Omarska 1996

“Rudnik Omarska” — Omarska Mine — lay buried beneath a sheet of ice and lies. Snowflakes, which muted all sound and draped the mine in virgin white, also covered over the history of this place. It was seven below zero, but my shivers did not come from the cold. Children played on sleds in the yard that was once a tarmac killing ground. A couple of stray mongrels frolicked in the jaw of the hydraulic door that leads inside to the great rust-red hangar where the prisoners were once packed together.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Armed guards oversee staged lunch at Omarska concentration camp. Ian Williams, ITN, 6 August 1992

Three sentries stopped us as we tried to enter. Two of these men were from the village of Omarska. One of them, age 28, told us, “Nothing happened here.” He worked as a mine technician in 1992. “It was a mine, up to the end of the year,” he said, “so how can it have been a camp in August of that year? I know, I was here.” I believed he had been there, at least. “I blame the journalists,” said his 24-year-old friend. “The Muslims paid the media, and they forged the television pictures, anyone could do that,” he said. We asked them their names and the mine technician was suddenly harsh. “We had a nice chat, but no names. They are a secret. The Muslims know me, and I know them. But they have to produce evidence of what I did. These days, they can just pick you up and take you to The Hague.” We asked if they knew Dusko Tadic and they replied, “Not well. He had a nice cafe…there was no camp here.”

Next to the mine is the Wiski Bar, in the shadow of the accursed hangar, alongside the railway lines. Prisoners were brought here in boxcars that now sat rusting and idle on the tracks. If the Madonna record that was playing had not been too loud, these people, sipping coffee and chatting, would have been able to hear the screams. I thought of Daniel Goldhagen’s book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners, which explores the terrifying notion that whole societies — not just select individuals — are complicit in such crimes. The idea that everyone bears some degree of guilt seemed to make sense in this place, but to dwell on this could become the stuff of madness, so I set off in search of the individuals.

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Omarska concentration camp prisoners at staged lunch. Penny Marshall, ITN, 6 August 1992.

Four years ago, we were greeted in Pale on our way to Omarska by Radovan Karadzic’s deputy president, the impish professor Nikola Koljevic. After we found the camps in 1992, he looked me up in Belgrade and invited me out for tea and cakes. I thought back on that conversation. “So you found them!” he had laughed, squeakily. “Took you a long time didn’t it? Ha ha! All of that, happening so near Venice! And all you could think about was poor Sarajevo! None of you ever had your holidays in Trnopolje did you?” he asked.

This time, I found him in his office in baleful Banja Luka, overlooking a gray day and a square where a new church will be built when there is money. He stared down at the people trudging through the slush of their town from which the Muslims have been banished. Banja Luka has “won” its war — every mosque has disappeared without a trace. Koljevic talked about the racial memory and epic poetry of the Serbs, and how the latest carnage will go down in Serbian history as “the third great Balkan War.”

In the middle of his monologue, he lost his flow and began to mumble to himself. “Bones,” he muttered, “we were digging up the bones.” His eyes widened and he appeared hypnotized, his imagination ambushed by some memory. “The bones of our dead from 1941…we dug them up, to give them a proper burial,” he said. This was a reference to the macabre prologue to the war — the Serbian cult of exhuming their dead from the Second World War. “We found shoes, children’s shoes and school books. How much more human a shoe is than a bone,” he said. To me, it seemed he was clearly talking about some other bones, more recently buried. This was when mass graves were being hidden from prying Hague investigators. Koljevic suddenly came to his senses. “I was just trying to illustrate the psychology,” he said.

As I watched this man trawling his memory, I imagined that a dark psychodrama was unfolding in his head, that of the restless dead. He was exhuming the bones of his own dead from the Second World War, only to bury his enemies in fresh mass graves. Now he was exhuming them too, to hide them, while disinterring the new Serbian dead for another burial in land assigned to his people by the Dayton plan. By way of farewell, the professor recommended to us his current reading, Daniel Boorstein’s The Image. He read aloud from the foreword: “This book is about self-deception, and how we hide reality from ourselves.” Koljevic had done just that. He had not reckoned with anything, but instead, projected his own obsessive and disastrous racial memory onto his perceived enemies — the Muslims. The Serbian “cult of the victim” demanded that he create victims in the same way the Serbian experience in concentration camps under the Nazis demanded they create new concentration camps. When the perpetrators look into the mirror, they must see someone they can call their enemy, so they do not see themselves. When they look at history, they must contort it, so they do not see their actions. They must rewrite the history they defile. That is the very opposite of reckoning. Some time soon after our conversation, I learned that Professor Koljevic shot himself dead. Perhaps that was his moment of honesty, the moment he suddenly saw himself in the mirror, a reckoning of sorts.

As I continued my search for the individuals I had known four years earlier, I looked up Simo Drljaca. He was the police chief who physically escorted us to Omarska and then threw us out again. Now, four years later, he refused a meeting. But Milomir Stakic, a bulldog of a man, granted one. Ironically, he was a doctor and an attentive student of Professor Koljevic. In 1992 he had introduced himself as the mayor of Prijedor, in charge of Omarska. Now, he said there had been no camp at all. He said that ITN’s pictures were of “Serbs in Muslim camps.” An immediate, illogical negation followed, “Omarska was for Muslims with illegal weapons.” “Omarska was not a hotel,” he said as he managed his only smile, which was not an agreeable one, and concluded, “but Omarska was not a concentration camp.” This nonsensical blend of denial and vindication was typical in Prijedor and was the very opposite of reckoning.

Next, I found the final member of the “crisis committee” I had met with years ago, Milan Kovacevic. I found Kovacevic early in the morning at the Prijedor hospital where he now served as director. I was horrified to learn that he, too, was a doctor. In 1992 his eyes had been fiery with enthusiasm. They were still fiery now, but from some other, more haunted emotion. We went to his house where he extracted a bottle of homemade plum brandy from his cupboard. It had been a good year for plums, he explained. I did not remind him that we had met before.

He started to unfurl the psychodrama of his life story. He was not — as he had said in 1992 — born in Jasenovac, but had been taken there as a child. Having been brought up to believe that “all Germans are killers,” he had elected to go to Germany, of all places, to study anesthesiology, of all things. He returned to his native Yugoslavia, practiced medicine, became a fervent Serbian nationalist, deputy mayor, architect of ethnic cleansing and the creator and manager of Omarska, Trnopolje and Kereterm.

Initially, his certainty about the ends concealed his doubts about the means. “We [and the Muslims] cannot live together,” he said. When I asked if all of the burned-out Muslim houses along the road had been necessary, or a moment of madness, Kovacevic proceeded cautiously. “Both things,” he said, emboldened by a glass of brandy, “a necessary fight and a moment of madness…people weren’t behaving normally.” This came as a surprise since Bosnian Serbs, let alone their leaders, did not usually talk like this. I asked if it had all been a terrible mistake and he answered, “To be sure it was a terrible mistake.”

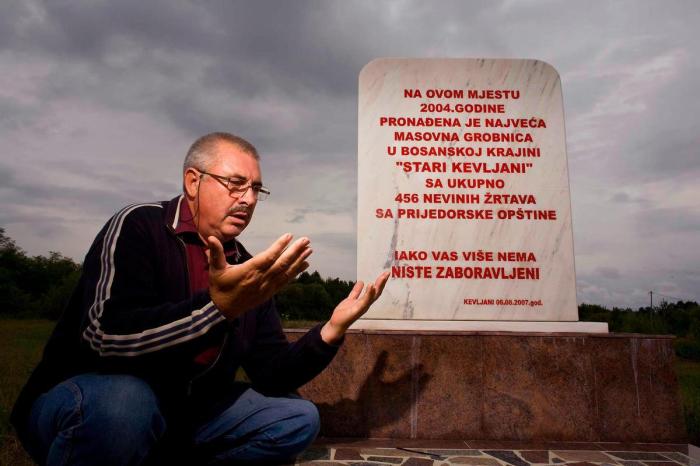

Bosnian Genocide (1992), Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) man prays above Stari Kevljani mass grave where Serb forces massacred 456 Bosniak women, children and elderly in 1992 (near Prijedor)

After a second glass, he continued, suddenly and unprompted: “We all know what happened at Auschwitz and Dachau, and we knew very well how it started and how it was done. What we did was not the same as Auschwitz or Dachau, but it was a mistake. It was planned to have a camp, but not a concentration camp.” Here was one of the men who created the gulag initiating this language. With the help of a third glass, the anesthetist ploughed boldly on; “Omarska was planned as a reception center. But then it turned into something else.” He admitted that he had never had this conversation before, except with himself. Another glass to steel the spirit, and unsurprisingly, his own childhood in Jasenovac came back to mind. “Six hundred thousand were killed in Jasenovac,” he mused, quiet for a moment.

But Jasenovac was run by Croats, I said; why did the Serbs now turn on someone else, the Muslims? Kovacevic straightened himself and said, “They committed war crimes, and now it is the other way around.” In Omarska, he said, “there were not more than 100 killed, whereas Jasenovac was a killing factory.” I suggested that 100 was a low figure. “I said there were 100 killed,” he specified, “not died. You would have to talk to the doctors about how many died.” But you are a doctor, I replied, and then asked again, “How many died?” Kovacevic threw off all caution, “Oh, I don’t know how many were killed in there. God alone knows. It’s a wind tunnel, this part of the world, a hurricane blowing to and fro.”

By now the cheap wood-paneled room was steaming with the exhaled fumes of fast-disappearing cigarettes, a fifth drink and talk of death. I asked the doctor who planned this madness. “It all looks very well-planned if your view is from New York,” he replied. And he edged forward on his seat as if to whisper some intimate piece of personal advice. “But here, where everything is burning, and breaking apart in peoples’ heads…this was something for the psychiatrists. These people should all have been taken to the psychiatrist. But there wasn’t enough time.”

In 1992, Kovacevic did not hide his role in operating Omarska, Trnopolje and the other camps. But, I asked, what about now? Were you part of this insanity, doctor? He replied with surprising calm: “If someone said that I was not part of this collective madness, then I would have to admit that would not be true…but then I would want to think about how much I was a part of it.” He continued, “We cannot all be the same, even within the madness…but, if things go wrong in this hospital, then I am guilty.” He said he had left political life “because I saw many bad things. If you have to do things by killing people, well…that is my personal secret…now my hair is white, now I don’t sleep too well.”

The Hague, July 1998

I was halfway through my first week in the United States, driving in the high desert of New Mexico early one July morning, when I switched on National Public Radio. A news report said that a unit of British soldiers had shot Simo Drljaca dead and had arrested another man, who was apprehended at the Prijedor hospital. The bulletin did not give the second man’s name, but I didn’t need to be told. I had a feeling I would be called back to The Hague again.

The tribunal had changed since its eager, early days in 1996, and so had the atmosphere in The Hague. The institution had become burdened by the kind of bureaucracy that infuses the United Nations like a contagion. Defense witnesses were now holed up at the comfortable Bel Air while the victims testifying for the prosecution were farmed out to cheap boarding houses on the coast. But the committed few were still working hard and the moral outrage of the best prosecutors — some of the finest people in the world — fueled them on. Furthermore, one of the middle managers of the Omarska camp was about to be tried.

It was a look of vitriolic hatred I shall never forget that Milan Kovacevic threw at me across the courtroom last July. He was now a shadow of his former self — bespectacled, yellowed, shriveled, clearly ill. His lawyers made it clear that this was now personal and political as well as legal. One defense lawyer told a reporter from the New York Times that I would be “roasted alive.” The lead lawyer, Dusan Vucicevic, said I would “never work again, and no one will ever read his books.”

As I was cross-examined, over the course of three days, it felt a bit like being in that Ingmar Bergman film The Seventh Seal, in which a man plays chess with death for his soul. In many ways, those three days under intense, but inept, cross-examination were more testing — and certainly lonlier — than any moment of the war itself. At one point during this intended “roasting alive,” I was instructed by the judges to read aloud my notes from the interview with Kovacevic. That seemed perfectly reasonable, but then the lawyers demanded to see all my notebooks and insisted on seeing pages adjacent to the Kovacevic interview to establish “context.” They dove at an address and telephone number written in the margin demanding to know whose details I had jotted down. My colleagues’ warnings echoed in my ear. The phone number was extremely sensitive, indeed — its owner in clear danger from these vultures. Sure enough, questions about fictitious camps came up. Kovacevic’s lawyers called it “the barbed wire question.” This was fortuitous, since it enabled the prosecution to ridicule the argument made by defense lawyer Jovan Stojic with pictures showing quite clearly that Alic and his fellow prisoners were exactly that.

A few days after my testimony, I heard that Kovacevic had died of a heart attack. Only Kovacevic’s God knows whether this was medicine or reckoning. Needless to say, the tribunal’s press office received phone calls from Belgrade calling it murder and in the Serbian press, I was accused of having a part in it.

Both sides in the trial felt Kovacevic’s death had cheated justice. To his own people and the defense, he became an ensnared martyr. To the prosecution, he died a man who robbed them of the first ever conviction for genocide in an international court. To me, he died a man of sufficient intelligence — and maybe, religion — to have had a flash of drunken remorse over the monstrous deeds he had committed. He was dragged back into the fold of his odious ideology by the needs of lawyers and out of his own desire not to spend the rest of his life in jail. I was too hardened now, by war, to have been sad that day. Once you cross the line and disregard neutrality, your hope for justice is invested in this reckoning. It is not a game, nor an academic debate — but part of a constant dialogue with death that extends from war into peace.

To Kovacevic’s victims — the thousands he incarcerated and the tens of thousands whose lives he destroyed forever — he died a war criminal. To them, his rotten soul is drowning in some nether region that is anything but heaven.

Beyond Neutrality

Neutrality, over evils like Omarska, is a pernicious thing and like death, it infuses the peace. The shocking thing in the aftermath is the absence of reckoning, the gnarled desire of spectators from afar to seek excuses for the aggressor. This is what denies peace in the Balkans. It is remarkable, for those of us who witnessed the war, to find “experts,” who have no idea what it is like to see women and children blown to bloody pieces, fussing over minor details of the war. They pick at any particularity that might shore up a case to prove the victims, the Muslim people, in some way culpable, and the Serbian perpetrators of the carnage aggrieved and therefore justified. To suggest that the Muslims of Bosnia should have been protected from the genocidal madness unleashed upon them is now viewed as simplistic and mundane.

Why is this? One would like to believe that the West feels so guilty about not having intervened that a curious alliance of intellectuals, career diplomats and United Nations bureaucrats are desperately striving to convince themselves that it was not necessary to respond. By justifying such a view, they gain absolution. I fear that this is optimistic. More convincing, and more depressing, is the specter of “victim-hatred.” I call it “post-Holocaust stress syndrome.” These days, one has to take the most contrary position possible to be original or interesting. The best way to get attention in this fatuous way, in the wake of such violence, is to blame the victim for his or her suffering and to side with the bully. For some spine-chilling reason, it has become boring to say that right is right, wrong is wrong and evil is evil.

In the small cottage industry that has developed around the carnage in Bosnia, of which The Hague is part, by no means are all of the reflections this pernicious. Some bold and valuable work has been accomplished. John Shattuck, U.S. human rights envoy, swept through Omarska surrounded by a platoon of writers from glossy magazines who produced diligent work. Mass graves and massacres, killers and victims have become the subject of television documentaries, many of them marvelous, and also the estimable movie Welcome to Sarajevo. Law schools and human rights activists pore over the crimes committed, with laudable zeal and commitment. Millions of words are exchanged at conferences, in books and in journals, some by people who know what they are talking about and others by people who don’t.

All this interest is welcome now, but where was it in 1992? During the war, when there was everything to be done, there was little in the way of lasting, serious interest. Now it is too late, and there is nothing really left to do: only to learn and make sure it does not happen again. At the time of writing, there are signs in Kosovo that not only has nothing been learned, but we are in for a repeat performance of yet more grotesque appeasement and “neutrality” from the west.

Nearly three decades ago, closer in time to the Holocaust than now, George Steiner predicted this nightmare of self-deception:

Our threshold of apprehension has been formidably lowered. When the first reports of the death camps were smuggled out of Poland, they were largely disbelieved; such things could not be taking place in civilized Europe, in the mid-twentieth century. Today, it is difficult to conjecture a bestiality, a lunacy of oppression or sudden devastation, which would not be credible, which would not soon be located in the order of facts. Morally, psychologically, it is a terrible thing to be so unastonished.5

Neutrality is still the currency of the Western response to calamity and genocide — nowhere more evident than in the media. It appears that after all the huffing and puffing, the spilled blood and broken promises, the graves and families torn asunder, the whimsy and the caprice, the lying and betrayal, the most urgent thing for the West to reckon with is the fact that almost nothing has been learned.

Court was ready to find Slobodan Milosevic Guilty of Bosnian Genocide

The trial of former Serbian leader, Slobodan Milosevic, would end in a guilty verdict on all 66 counts of genocide and war crimes, had he not died in prison.

Slobodan Milosevic was charged by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia with 66 counts of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes in indictments covering war in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo as Yugoslavia disintegrated.

On 11 March 2006, Milosevic died in his cell while being tried for war crimes at the Hague Tribunal. He suffered from a heart condition and high blood pressure. He died only months before a verdict was due in his four-year trial at the Hague. No further action was taken on the case.

However, the Trial Chamber, on 16 June 2004, rejected a defense motion to dismiss the charges against Slobodan Milosevic for lack of evidence, thereby confirming, in accordance with Rule 98bis, that the prosecution case contains sufficient evidence capable of supporting a conviction on all 66 counts, including the genocide against Bosnian Muslims.

In a rule 98bis proceedings on 16 June 2004, the Trial Chamber found, with respect to the specific charges regarding genocide, that:

“(3) the Accused was a participant in a joint criminal enterprise, which included members of the Bosnian Serb leadership, to commit other crimes than genocide and it was reasonably foreseable to him that, as a consequence of the commission of those crimes, genocide of a part of the Bosnian Muslims as a group would be committed by other participants in the joint criminal enterprise, and it was committed;

(4) the Accused aided and abetted or was complicit in the commission of the crime of genocide in that he had knowledge of the joint criminal enterprise, and that he gave its participants substantial assistance, being aware that its aim and intention was the destruction of a part of the Bosnian Muslims as group;

(5) the Accused was a superior to certain persons whom he knew or had reasons to know were about to commit or had committed genocide of a part of the Bosnian Muslims as a group, and he failed to take the necessary measures to prevent the commission of genocide, or punish the perpetrators thereof.”

Serbs Repeat Massacre, 70 Bosniak Civilians Burned to Death (27 June 1992)

Photo: Bosnian Serb Milan Lukic was a leader of the paramilitary group responsible for burning alive at least 140 Bosniak civilians – including babies and children – in Visegrad during the Bosnian genocide (1992-95)

Two weeks after the Serbs burned alive a group of 70 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) women, children and elderly on the Pionirska Street in Visegrad (adjoining municipality south of Srebrenica), they repeated their ghastly crimes again.

On 27 June 1992, a group of Serb paramilitary thugs, led by police officer Milan Lukic, detained a new group of about 70 Bosniak civilians – women, children and elderly men. They locked them in abandoned house of Meho Aljic in the settlement of Bikavac in Visegrad.

All the exits had been blocked by heavy furniture and a garage door was also placed against a door to prevent escape. Then, the house was set on fire.

They burned Bosniak women, children and elderly alive. The skin of the victims melted and horrible screams could be heard blocks away. Only one woman survived. Her name is Zehra Turjacanin. Here is her story: Read the rest of this entry »

Bosnian Genocide (1992-95) Confirmed by Four International Judgements

OTHER THAN SREBRENICA: Srebrenica is one of four legally validated genocides that occurred in Bosnia-Herzegovina during the 1992-95 Serbian aggression. Other notable cases of the Bosnian Genocide include international judgements in the following trials: Prosecutor v Jorgic (Doboj region), Prosecutor v Djajic (Foča region), and Prosecutor v Sokolovic (Kalesija/Zvornik region).

All three cases were tried in Germany — at the request of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) — to ease caseload of the ongoing trials at the Hague. Both Nikola Jorgic and Maksim Sokolovic were convicted of genocide (other than Srebrenica); Novislav Djajic was acquitted, but the court confirmed that genocide against the Bosniak population was committed by the Serb forces in eastern Bosnian municipality of Foca.

Bosnian Genocide Memorial in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York – the Largest Christian Church in the World

Dedicated to the Bosnian Genocide Read the rest of this entry »

ICJ Judge, Serbia’s involvement in Srebrenica Genocide supported by massive and compelling evidence

Case: Bosnia v. Serbia

Judgement: Dissenting opinion of Judge Al-Khasawneh, Vice-President of the International Court of Justice.

The Court’s jurisdiction is established – Serious doubts that already settled question of jurisdiction should have been re-examined – SFRY’s United Nations membership could only have been suspended or terminated pursuant to Articles 5 or 6 of the Charter; Security Council and General Assembly resolutions did not have the effect of terminating the SFRY’s United Nations membership – The FRY’s admission to the United Nations in 2000 did not retroactively change its position vis-à-vis the United Nations between 1992 and 2000 – Between 1992 and 2000, the FRY was the continuator of the SFRY, and after its admission to the United Nations, the FRY was the SFRY’s successor – The Court’s Judgment in the Legality of Use of Force cases on the question of access and “treaties in force” is not convincing and regrettably has led to confusion and contradictions within the Court’s own jurisprudence – The Court should not have entertained the Respondent’s highly irregular 2001 “Initiative” on access to the Court, nor should it have invited the Respondent to renew its jurisdictional arguments at the merits phase.

Serbia’s involvement, as a principal actor or accomplice, in the genocide that took place in Srebrenica is supported by massive and compelling evidence – Disagreement with the Court’s methodology for appreciating the facts and drawing inferences therefrom – The Court should have required the Respondent to provide unedited copies of its Supreme Defence Council documents, failing which, the Court should have allowed a more liberal recourse to inference – The “effective control” test for attribution established in the Nicaragua case is not suitable to questions of State responsibility for international crimes committed with a common purpose -The “overall control” test for attribution established in the Tadić case is more appropriatewhen the commission of international crimes is the common objective of the controlling State and the non-State actors – The Court’s refusal to infer genocidal intent from a consistent pattern of conduct in Bosnia and Herzegovina is inconsistent with the established jurisprudence of the ICTY – the FRY’s knowledge of the genocide set to unfold in Srebrenica is clearly established – The Court should have treated the Scorpions as a de jure organ of the FRY – The statement by the Serbian Council of Ministers in response to the massacre of Muslim men by the Scorpions amounted to an admission of responsibility – The Court failed to appreciate the definitional complexity of the crime of genocide and to assess the facts before it accordingly. Read the rest of this entry »

Doboj Genocide, Serbs Raped 2,000-2,500 Bosniak & Croat Women & Children

Excerpt from “Mass rape: the war against women in Bosnia-Herzegovina” By Alexandra Stiglmayer, Marion Faber

“I saw about seven or eight little girls who died after they were raped. I saw how they took them away to be raped and then brought them back unconscious. They three them down in front of us…”

The Rape Camp in Doboj

According to the statements of three women, there was a women’s camp in the northern Bosnian town of Doboj in which approximately 2,000 Bosniak and Croatian women as well as a few children were detained in May and June 1992 (three years before the Srebrenica genocide. Note that Doboj Genocide is another legally validated case of genocide in Bosnia.). This number is very high, and I have discussed it at length with the women. They insist it is correct and say that the gymnasium of the Djure Pucar Stari school in which they were housed was very big, that international handball tournaments were held in it previously, that it even had tiers of seats, and that it was “completely overcrowded.”

“We couldn’t move without stepping on somebody,” says forty-year-old Kadira.” “There might even have been 2,500 women.” Read the rest of this entry »

Element of Bosnian Genocide, Systematic Rape of Muslim Women

A pattern of crime: Serbian soldiers repeatedly raped Bosniak women and girls as young as 6 and 7.

January 04, 1993.

NEWSWEEK

About all she has left is her name, which she prefers to keep to herself, and the shocking memories of last July. That’s when Serbian troops stormed the northwest Bosnian village of Rizvanovici, and S., a 20-year-old Bosniak [Bosnian Muslim] woman with a ponytail, was rounded up with 400 other women in the yard of a neighbor’s house. Two soldiers, wearing camouflage uniforms and Serbian crosses around their necks, picked S. and her friend I. out of the crowd.

“They brought us to an empty house and there they did what they wanted to do,” says S. dully. “First we had to excite them and then we had to satisfy them.” Afterward the Serbs traded partners. The girls had been virgins. “They were laughing at us,” S. recalls. “They said we were pretty girls and [that] we saved ourselves for them.”

Her ordeal didn’t end there. After being raped and dumped at the yard, one of the soldiers came back to bring S. to his commander. “He told me to take off my clothes and to lie down on the bed,” she says. “Then he did the same thing. Read the rest of this entry »

Holocaust Survivor: Forty-thousand Bosnian Muslims Targeted for Extinction in Srebrenica